- Home

- T. Kingfisher

Bryony and Roses

Bryony and Roses Read online

CONTENTS

Copyright Information

Praise for T. Kingfisher

Title Page

Dedication

A Note About Books and Roses

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Acknowledgments

Other Works

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to persons, places, plants, poets, events, or actual historical personages, living, dead, or trapped in a hellish afterlife is purely coincidental.

Copyright 2015 Ursula Vernon

All Rights Reserved

Published in the United States by Red Wombat Tea Company

Artwork by Ursula Vernon

Praise for “Toad Words”

“…a book of re-told fairy tales, all in the quirky, matter-of-fact-in-the-face-of-total-nonsense style that I’ve always loved. They’re often dark, sometimes sad, but always endearing, even when they’re disturbing.”

—Pixelatedgeek.com

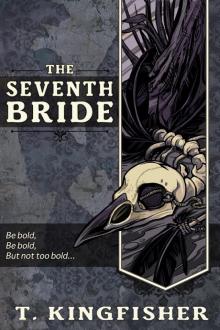

Praise for “The Seventh Bride”

“A brilliant re-telling of the "Bluebeard" fairy tale, The Seventh Bride captures the horror of the original story, but Kingfisher creates a wonderful character in Rhea.”

—Alexis Lantgen, The Wise Serpent

For my mom,

from whom I probably

inherited the gardening

thing

A NOTE ABOUT BOOKS AND ROSES

When I was in my early 20s, I picked up a book called Rose Daughter by Robin McKinley. It was a retelling of Beauty and the Beast and it was wonderful.

In addition to being an amazing author, McKinley did two things very right. One of them I can’t reveal without ruining the ending. The second involves the rose.

Some elements are fairy-tale canon, of course, and figure in almost every retelling—the sisters, the merchant who loses his wealth and hopes to regain it, the house of invisible servants that grant every desire, the Beast who asks Beauty to marry him every night, and of course, the stolen rose.

(In the very lengthy French version, which is…something else…all these elements are jumbled together with trained monkey servants and parrots and devices that allow one to spy on anyone else in the world. The Beauty and the Beast story take up only the first third, which is mostly concerned with fairy politics. But even then, there’s still a rose.)

Rose Daughter returned the rose to center stage and made Beauty a rose-loving gardener.

At the time I read it, I was myself a frustrated gardener. I had discovered that gardening was in my blood but had no garden. I was trying to save myself with hanging baskets and houseplants, wedged into a tiny apartment with very little sunlight, and it was not going well.

Rose Daughter was a window into a world that I desperately wanted. I loved it. I read it until my first copy fell apart.

Years passed. I moved out of the apartment and into a series of larger rentals and finally a house and a garden in North Carolina.

North Carolina is not a great climate for roses. They get mildew and black spot and very strange diseases. I planted roses and watched them die.

I went to native roses—fierce, rugged, unstoppable plants, with canes like barbed wire. They grew. Too well. I went from dead roses to hacking back runners that were popping up in flower beds twenty feet away. They were beautiful for only about ten minutes at a time and they did not smell like much of anything and they wanted to eat the world.

After a year or two, it began to occur to me that I didn’t actually like roses very much.

After three or four years, I sat down and began to write a book. It was also retelling of Beauty and the Beast, and in a very different way, it was also about roses…and about rutabagas, and basil, and mint, and plants that I knew from my own life as a gardener.

All of which is a long way of saying that this book would probably not have existed without McKinley’s Rose Daughter, and I am very grateful to her for writing it. It was a book I needed very much at the time, and if I had not needed it so badly, I don’t know that I would have found myself needing to write this one.

I know it’s probably a bad idea for an author to tell you, in an introduction, that you should go read that other book, but if you love the fairy tale—or gardens—I cannot recommend it highly enough. Regardless of how you feel about roses.

T. Kingfisher

Pittsboro, NC

May, 2015

CHAPTER ONE

She was going to die because of the rutabagas.

Bryony pushed her cloak back from her face and looked up. The space between Fumblefoot’s ears had become her entire world for the past half-hour, and she was a little surprised at how large the forest was when she finally lifted her eyes.

Unfortunately, it was all covered in a thick blanket of snow.

Her pony continued plodding forward, the snow wet and sloughing around his hooves. Even with her teeth chattering, Bryony could appreciate the beauty of the snow—fat flakes falling in a steady, business-like manner, black tree trunks fading into soft grey, the way snow piled up on top of the evergreen branches and bore them down to the ground.

It was a pity that all that beauty was going to kill them.

The pony staggered a bit. Bryony patted his shoulder as he got his feet back underneath him. It might be a sign of exhaustion, but then again, Fumblefoot came by his name honestly, and he could just be clumsy.

Please just be clumsy, old fellow.

She wished that she could get off and lead him, but once she did that, it was only a matter of time.

She hadn’t felt her feet in nearly an hour. Even if Fumblefoot somehow staggered onto the road to the village, she suspected that she’d be down a couple of toes by the time they made it home.

Farewell, little pinkie toes. I can’t say I ever really appreciated you, but I suspect that I will miss you very much once you’re gone.

Rutabagas. Of all the stupid things to die for.

The problem with rutabagas was that they liked a long growing season if they could get it, and the earlier you planted them the better. Bryony had no great love of rutabagas—they were basically somewhat insipid turnips, fit only for stews and roasts—but she’d also never had any great success growing them, and that was a direct affront to her gardening skills.

When her friend Elspeth in Skypepper Village had sent word that she had some particularly hardy rutabagas last year, and would be happy to share the seeds, Bryony had saddled up Fumblefoot and made the five-hour journey to Skypepper. It was a little early in the spring, sure, but you really couldn’t get the seeds in the ground too quickly, and there were all sorts of ways to coax the seedlings along if it looked like it was going to frost.

Bryony’s lips twisted sourly. She tucked her gloved hands under her arm

pits, leaving the reins looped over the saddle horn. (Fumblefoot would have landed flat on his face if he tried to bolt at the best of times. He would no more have tried to run in the snow than he would have tried to fly.)

Frost. Heh.

Freakish late season blizzard, on the other hand…

Most of her plants would probably do fine, even if her sister hadn’t gotten out and covered them. Sadly, Bryony and Fumblefoot wouldn’t fare nearly so well as the plants.

Fumblefoot stumbled again. The wind was beginning to pick up. Bryony watched the snowfall between the pony’s ears, and saw it begin to fall slantwise. When she lifted her chin off her chest to look around, the forest seemed smaller, closed in, as if they moved through a series of snowy rooms.

Beets, now, those were useful. Beets you could do something with. Tomatoes, definitely. It went without saying that a good tomato was worth dying over—if not your personal death, then certainly the neighbor’s, who would insist on growing a tomato the size of a baby’s head and then waving a hand and saying “Oh, well, nothing to it, really, I just put ‘em in the ground and give ‘em a drop of water now and again.”

Obviously if such a neighbor was interred in the compost heap, no jury of gardeners would ever convict you.

Corn, too. Sweet corn was a glorious thing, particularly in summer, and while Bryony would not personally have been inclined to die for it, there were stories that whole civilizations were in the habit of sacrificing people to ensure the corn harvest. And wheat was so tied in with blood that even now if you went too far up into the hills at the wrong time of year, you’d best check the scarecrows very carefully to make sure that one of them wasn’t a former travelling salesman.

Bryony sighed. Nobody in the history of the world had ever sacrificed anybody to the rutabagas. The issue simply did not arise.

She wiggled her fingers inside her gloves, yanking them free of the fabric and folding them up against her palm to try to warm them. She mostly succeeded in making her palms colder.

Her sisters were going to miss her. Bryony felt a pang thinking of them. Holly was probably going to the window every few minutes and pushing the curtains aside to look for her. Iris was likely sitting beside the fireplace, working on her embroidery and making endless cups of tea.

At least it probably won’t hurt, she thought glumly. I hear you feel really warm right before you freeze to death.

It was hard to get upset. She was too cold. Her eyelashes had ice on them, and if she cried it would freeze on her cheeks. It was easier simply to tuck her hands in her armpits and let her chin sink to her chest and let Fumblefoot lead them through the woods. He was probably no better at finding the road than she was—Fumblefoot was a very inferior pony, or else Bryony and her sisters would never have been able to afford him—but the world was nothing but snow now, and anything resembling landmarks had vanished under white.

She tried to summon some anguish over her impending demise, but her mind rapidly wandered to the rutabaga seeds and then to the garden, and from there death could not compete.

I’ll miss the garden this spring. Damnit. I hope Holly will remember that she needs to spread manure on it—Iris won’t, Iris hates the very thought of manure. And someone has to weed the bee balm back, or it’ll eat the whole flowerbed, and this was the year I was really hoping that the sage would take off…

Her thoughts continued in this vein for quite some time, punctuated occasionally by rubbing her nose (which was very cold, and in the way of cold noses, dripping) until she realized that Fumblefoot had stopped walking and lifted her head.

They’d found an impossible road.

CHAPTER TWO

It wasn’t the main road. The road between Skypepper and Lostfarthing was broad enough for two wagons to pass abreast. This was narrower, wide enough for two horses perhaps, and there was a stone wall running along the right hand side.

The problem was that there wasn’t any such road in the woods between Skypepper and Lostfarthing. There wouldn’t be any point to it. Cutting the woods was strictly forbidden by royal decree, and there was a certain understanding among the villagers that it was in everybody’s best interest if the king never had reason to send someone around to check on the forest. Poaching here was not so much a crime as a way of life, and if foresters and game wardens showed up demanding to know where all the trees had gone, a lot of people were going to go very hungry before they went away again.

There were a lot of deer in the woods—and elk and wolves and even a few of the rare forest bison (which was why it was a royal preserve in the first place.)

What there most certainly wasn’t was a high stone wall, inset with a pair of iron gates with twining wrought-iron roses.

Saying they didn’t exist did nothing to negate the fact that Bryony was currently looking at them.

They were lovely gates. An inch of snow sat atop every metal curve, giving the iron roses substance. The stone pilings on either side of the gate rose taller than her head, and were topped with two stone horses, their rearing bodies strangely elongated by the coat of snow.

Just visible through the iron gates was the grey outline of a manor house.

Bryony sat on the pony and stared.

There could not be a manor house. There had never been a manor house anywhere near Lostfarthing. Nobles did not come to Lostfarthing. It was not possible for a noble to disgrace themselves badly enough to be exiled this far east. The Duke of Entwood had been convicted of black magic, cannibalism, and high treason, and while he’d been burned at the stake, his heirs had only been sent as far east as Blue Lady, which was still two day’s travel west of Skypepper.

The questionable delights of a village of a hundred and fifty souls was not sufficient to attract aristocrats in the summer, let alone during the short but vigorous winters, when the road was often snowed closed for a week or more at a time.

Nevertheless, there were gates. Insisting that there could not be gates did not make them go away. And looming beyond them, a grey shadow on the grey sky, was a distant roofline.

“My b-brain has frozen, and I’m hallucinating,” Bryony said. Fumblefoot put an ear in her direction.

The snow continued to fall thick and fast. Bryony clumsily pulled her glove back on with her teeth and slid off the pony’s back. The snow came up halfway to her knees.

Perhaps it was a convent. That made more sense. There was an order of nuns in Lostfarthing, the Order of St. Agnes, and they had been there forever. This was certainly not the current convent, which was smaller and had a much-mended deer fence instead of a wall, but it was just barely possible that they had once had a bigger convent in the woods—or perhaps there had been another order of nuns or monks or other serious and celibate folk—and here it was. The king frequently granted land to religious orders out on the fringes of the kingdom, because it got them out of the capital and meant that they stopped demanding things.

“That’s it,” said Bryony to the pony. “It’s an old abandoned convent. The gates and the wall have held up very well, and I admit I’ve never heard of one out here, but that’s the only possible explanation.” She wiped her gloved hand across her eyelashes to clear the film of ice. “It’s probably in ruins, but if there are a few walls still standing, maybe we can get out of the wind long enough not to die.”

She reached out a hand to push the wrought-iron roses, and the gate swung open as silently as snowfall.

“Very w-well oiled ruins,” she said to Fumblefoot, who looked at her as if she were crazy.

She picked up the pony’s reins and led him through the gate. When she turned back to shut the gate—to keep out what? Snow-crazed bandits?—she felt her stomach give a funny little flip and watched the gate close by itself.

“Very w-well-weighted,” she said. “Yes. One of the nuns was clearly a m-m-master ironworker.”

Fumblefoot put his cheek against her shoulder and gazed at her mournfully, clearly hoping that if he stared long enough, she would produce war

mth and oats and perhaps a stable.

“C-c-c’mon, fella, let’s get ins-s-side.” She gathered up the reins and looked up at the outline of the large building. If she had been warmer, she might have been a little bit afraid, but she was going to freeze to death soon, and her teeth were chattering so loudly that it was difficult to keep her thoughts together. They seemed to rattle apart before they could get anywhere.

Not being able to feel her feet did not make walking any easier. She floundered in the snow, and Fumblefoot slipped and limped along behind her.

It was a long way to the building. She could not tell what material the pathway was made from, underneath the crunching snow, but some square objects lined the pathway, their edges barely visible under the drifted snow. More walls?

When she strayed to one side and brushed her gloved hand across one, branches poked and caught under the snow, and she caught a glimpse of green.

Her lip curled. Boxwoods. Typical. She’d never liked boxwoods even before they had moved to Lostfarthing—no fruits, barely any flowers, all the purpose they served was to be chopped and clipped into ridiculous shapes for the amusement of aristocrats.

Bryony had slipped and slid down the pathway, Fumblefoot plodding along, for a good half-minute when it occurred to her that boxwoods needed pruning (yet another reason that she was not fond of them) and unless the abandoned convent still kept a gardening staff, the neat cubical hedge would be a thicket in two seasons.

Ah. Hmm.

She glared at the drifts concealing the hedge.

Maybe they’re…slow-growing boxwoods. Dwarf boxwoods. Only need pruning every hundred years. Bryony grinned sourly to herself. Hey, let’s take cuttings, we’ll breed them and sell them to aristocrats in the capital for a fortune…

Paladin's Strength

Paladin's Strength The Twisted Ones

The Twisted Ones The Hollow Places

The Hollow Places Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel

Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel Swordheart

Swordheart Jackalope Wives And Other Stories

Jackalope Wives And Other Stories A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking

A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking Minor Mage

Minor Mage The Halcyon Fairy Book

The Halcyon Fairy Book Bryony and Roses

Bryony and Roses The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War

The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War

Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War The Raven and the Reindeer

The Raven and the Reindeer Summer in Orcus

Summer in Orcus The Wonder Engine

The Wonder Engine Seventh Bride

Seventh Bride Toad Words

Toad Words Nine Goblins

Nine Goblins