- Home

- T. Kingfisher

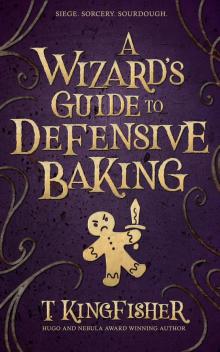

A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking

A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking Read online

Praise for T. Kingfisher

"Dive in...if you are looking to be charmed and delighted."”

Locus

“…[A] knack for creating colorful, instantly memorable characters, and inhuman creatures capable of inspiring awe and wonder.”

NPR Books

"The writing. It is superb. T. Kingfisher, where have you been all my life?"

The Book Smugglers

“…you walk away going ‘Damn, that was good but there's a new layer of trauma living inside me.’”

KB Spangler, DIGITAL DIVIDE

A Wizard’s Guide To Defensive Baking

T. Kingfisher

Copyright © 2020 by T. Kingfisher

Ebook by Red Wombat Studio

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Created with Vellum

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by T. Kingfisher

One

There was a dead girl in my aunt’s bakery.

I let out an undignified yelp and backed up a step, then another, until I ran into the bakery door. We keep the door open most of the time because the big ovens get swelteringly hot otherwise, but it was four in the morning and nothing was warmed up yet.

I could tell right away that she was dead. I haven’t seen a lot of dead bodies in my life—I’m only fourteen, and baking’s not exactly a high-mortality profession—but the red stuff oozing out from under her head definitely wasn’t raspberry filling. And she was lying at an awkward angle that nobody would choose to sleep in, even assuming they’d break into a bakery to take a nap in the first place.

My stomach made an awful clenching, like somebody had grabbed it and squeezed hard, and I clapped both hands over my mouth to keep from getting sick. There was already enough of a mess to clean up without adding my secondhand breakfast to it.

The worst thing I’ve ever seen in the kitchen was the occasional rat—don’t judge us, you can’t keep rats out in this city, and we’re as clean an establishment as you’ll ever find—and the zombie frog that crawled out of the canals. Poor thing had been downstream of the cathedral, and sometimes they dump the holy water a little recklessly, and you get a plague of undead frogs and newts and whatnot. (The crawfish are the worst. You can get the frogs with a broom, but you have to call a priest in for a zombie crawfish.)

But I would have preferred any number of zombie frogs to a corpse.

I have to get Aunt Tabitha. She’ll know what to do. Not that Aunt Tabitha had bodies in her bakery on a regular basis, but she’s one of those competent people who always know what to do. If a herd of ravenous centaurs descended on the city and went galloping through the streets, devouring small children and cats, Aunt Tabitha would calmly go about setting up barricades and manning crossbows as if she did it twice a week.

Unfortunately, to get to the hallway that led to the stairs up to Aunt Tabitha’s bedroom, I would have to walk the length of the kitchen, and that meant walking past the corpse. Stepping over it, in fact.

Okay. Okay. Feet, are you with me? Knees? Can we do this?

The feet and knees reported their willingness. The stomach was not so happy with this plan. I wrapped one hand around my waist and clamped the other firmly over my mouth in case it decided to rebel.

Okay. Okay, here we go…

I inched into the kitchen. I spent six days a week here, sometimes seven, running back and forth across the tile, flinging dough onto counters and pans into ovens. I crossed the kitchen floor hundreds of times a day, without even thinking about it. Now it seemed to be about a mile long, an unfamiliar and hostile landscape.

I had a dilemma. I didn’t want to look at the body, but if I didn’t, I might step on it—on her—and that just didn’t bear thinking about.

No help for it. I looked down.

The dead girl’s legs were splayed across the floor. She was wearing grimy boots with mismatched socks. That seemed very sad. I mean, it was sad that she was dead anyway—probably, unless she’d been a horrible person—but dying with mismatched socks seemed especially sad somehow.

I imagined her throwing the socks on, never thinking that a few hours later, an apprentice baker and half-baked wizard of dough would be tiptoeing past her and thinking about the condition of her footwear.

There was probably a moral lesson there somewhere, but I’m not a priest. I thought about becoming one once, but they don’t really like wizards, even minor wizards whose only talents are making bread rise and keeping the pastry dough from sticking together. Right about the time I gave up on hopes of joining the priesthood, Aunt Tabitha had taken me on in the bakery, and the siren song of flour and shortening pretty much sealed my fate.

I wondered what had sealed this poor girl’s fate. Her hair was mostly over her face, so it was hard to tell how old she was—and I wasn’t looking very closely—but I got the feeling she was young, maybe not much older than me. How did she wind up dead in our bakery? Somebody who was cold or hungry might conceivably creep into the bakery—it’s warm, even at night, since we bank the big stoves but we don’t put them out, and there’s always food around, even just the day-old stuff in the case. But that didn’t explain why she was dead.

I could see one of her eyes. It was open. I looked away again.

Maybe she slipped and hit her head. Aunt Tabitha always swears I’ll break my neck one of these days, the way I race around the kitchen like a flour-crazed greyhound, but it seems weird that you’d break into a bakery and then run around inside it.

Maybe she was murdered, whispered a traitorous little voice in my brain.

Shut up, shut up! That’s just stupid! I told it. People hold murders in back alleys and things, not in my aunt’s kitchen. And it’d be stupid to leave a body in a bakery. The whole city is built on canals, there are fifty bridges to a street, and the basements flood every spring. Who’d dump a body in a bakery when you could dump it in a perfectly good canal not twenty feet from the door?

I held my breath and stepped over the dead girl’s ankles.

Nothing happened. I wasn’t expecting anything to happen, but I was still relieved.

I looked straight ahead, took two more careful steps, then broke into a run. I knocked the door open with my shoulder and tore up the stairs, yelling “Aunt Tabithaaaaa! Come quick!”

* * *

It was four in the morning, but bakers are used to getting up at four in the morning, and the only reason that A

unt Tabitha was sleeping until the decadent hour of six-thirty was because her niece had finally been trusted to open the bakery in the last few months. (That’s me, in case you aren’t following along.) She’d been nervous about letting me take over, and I’d been really proud that nothing had gone wrong when I was opening.

This made me feel twice as guilty that a dead body had turned up on my watch, even though it wasn’t my fault. I mean, it’s not like I had killed her.

Don’t be stupid, nobody killed her. She just slipped. Probably.

“Aunt Tabithaaaa!”

“Gracious, Mona…” muttered my aunt from behind the door. “Is the building on fire?”

“No, Aunt Tabitha, I have discovered a dead body in our kitchen!” was what I meant to say. What came out was something more along the lines of “Aunt Body! There’s a Tabitha—the kitchen—dead, she’s dead—I—come quick—she’s dead!”

The door at the top of the stairs was flung open, and my aunt emerged, shouldering into her housedress. Her housedress is large and pink and has winged croissants embroidered across it. It’s quite hideous. Aunt Tabitha herself is large and pink but doesn’t have winged croissants flying across her except when wearing the housedress.

“Dead?” She narrowed her eyes down at me. “Who’s dead?”

“The body in the kitchen!”

“In my kitchen!?” Aunt Tabitha came barreling down the stairs at top speed, and not wanting to be trampled, I retreated in front of her. She brushed me aside, not unkindly, and went sideways through the door to the bakery. I followed, poking my head timidly around the doorframe and waiting for the explosion.

“Huh.” Aunt Tabitha put a fist on each generous hip. “That’s a dead body, all right. Lord save us. Huh.”

There was a long silence, while I stared at her back and she stared at the dead girl and the dead girl stared at the ceiling.

“Err…Aunt Tabitha…what should we do?” I finally asked.

Aunt Tabitha shook herself. “Well. I’ll go wake your uncle up and send him around to the constables. You start lighting the fires and put a tray of sweet buns on.”

“Sweet buns? We’re going to bake?”

“We’re a bakery, girl!” my aunt snapped. “Besides, never knew a copper who didn’t love a sweet bun, and we’ll be swarming with ’em before long. Better put on two trays, there’s a dear.”

“Err…” I drew myself together. “Should I start the rest of the baking then?”

My aunt frowned and tugged at her lower lip. “N-o-o-o…no, I don’t think so. They’ll be in and out and making a mess of things for a few hours at least. We’ll just have to open late, I suppose.”

She turned and stalked heavily away to roust my uncle.

I was left alone with the dead girl and the ovens.

I could get to one of the ovens easily enough, and I poked up the fire underneath and threw another log on. There’s a trick to keeping the ovens heated evenly, and it’s the first thing you learn. If you have spots that are too hot or too cool, your bread gets fallen spots and comes out looking lumpy and sort of squashed in places.

I couldn’t reach the other oven without stepping over her. After a moment’s thought, I threw one of our dishtowels over her face. It was easier somehow if I couldn’t see that one eye staring upward at nothing. I fired up the other oven.

Sweet buns are easy. I could make sweet buns in my sleep, and occasionally, at four in the morning, I pretty much do. I threw the dry ingredients together in a bowl and started whisking them together. I gazed up at the rafters so that I didn’t have any chance of seeing the body. There was a brief shine of eyes as a mouse looked down at me, then scurried across the rafters on his way back to his mousehole. (Having mice is actually a good thing, since it means we don’t have rats any more. Rats think mice are yummy.)

There were eggs on the counter and a big crockery jar of shortening in the corner. I cracked the eggs and separated out the yolks—perfectly, I might add—and dumped all the ingredients into a bigger bowl and started beating.

I heard the front door open and close, as Uncle Albert went out to get the constable. Aunt Tabitha was bustling around the front of the shop, probably getting ready to turn the first wave of customers away.

I wondered how many constables we’d get. A couple, right, for a murder? Murders are important. Would the body wagon come? Well, it’d have to, wouldn’t it? We couldn’t very well just set the body out with the garbage. The wagon would come, and then all the neighbors would think my uncle had died—nobody’d think Tabitha had died, of course, she was a force of nature—and they’d come around gossiping, and they’d find out there had been a murder—

Wait, when did I decide it was a murder? She just slipped, right?

I discovered that between not-looking at the dead girl and wondering about the constables that I’d been kneading the sweet bun dough for much too long. You don’t want to knead them too much, or it makes them tough. I stuck a floury hand in the dough and suggested that maybe it didn’t want to be tough. There was a sort of fizziness around my fingers and the dough went a little stickier. Dough is very amicable to persuasion if you know how to ask it right. Sometimes I forget that other people can’t do it.

I separated out a dozen evenly sized lumps of raw dough and set them on the wooden baking paddle, then shoved them into the oven with strict orders that they didn’t want to burn. They wouldn’t. Not burning is one of the few magics I’m really good at. Once, when I was having a really awful day, I did it too hard, and half the bread wouldn’t bake at all.

That was the sweet buns done. I wiped my hands on my apron and dipped a cup of flour out of one of the bins. There was one other task that had to be done, no matter what, whether there was one body in the kitchen or a dozen.

The steps down to the basement are slippery, because everybody’s basements leak. It’s amazing we still have basements. My father, who was a builder before he died, used to say that it was because there was another city down there, and people just kept on building upwards as the canals rose, so the basement floors were really the roofs and ceilings of old houses.

In the darkest, warmest corner of the basement, a bucket bubbled slowly. Every now and then one of the bubbles would pop, and exhale a damp, yeasty aroma.

“C’mon, Bob…” I said, using the sugary tones you’d use to approach an unpredictable animal. “C’mon. I’ve got some nice flour for you…”

Bob popped several bubbles, which is his version of an enthusiastic greeting.

Bob is my sourdough starter. He’s the first big magic I ever really did, and I didn’t know what I was doing, so I overdid it.

A sourdough starter is kind of a gloppy mess of all the yeast and weird little growing things that you need to make bread rise. The taste of the bread can change a lot depending on the starter. Most of them live for a couple of weeks, but in the right hands, they can stay alive for years. There’s one in Constantine that’s supposed to be over a century old.

When I first started working in my aunt’s bakery, I was just ten, and really scared that I’d screw something up. My magic tended to do weird things to recipes sometimes. So I was put in charge of tending her sourdough starter, which she’d been using since she started the bakery, and which was really important, because Aunt Tabitha’s bread was famous.

And…I don’t know if I gave it too much flour or too much water or not enough of either, but it dried up and nearly died. When I found that out, I was so scared that I stuck both hands into it (and it was pretty icky, let me tell you) and ordered it not to die. Live! I told it. C’mon, don’t die on me, live! Grow! Eat! Don’t dry up!

Well, I was ten, and I was really scared, and sometimes being scared does weird things to the magic. Supercharges it, for one thing. The starter didn’t die, and it grew. A lot. It foamed out of the jar and over my hands and I started yelling for Aunt Tabitha, but by the time she got there, the starter had reached the sack of flour I’d been using to feed it

and ate the whole thing. I started crying but Aunt Tabitha just put her hands on her hips and said, “It’s still alive, it’ll be fine,” and scraped it into a much bigger jar and that was the beginning of Bob.

I’m not actually sure if we could kill him any more. One time the city froze so hard that nobody could go anywhere, and Aunt Tabitha was stuck across town for three days and I couldn’t get down the block, and nobody fed Bob. I expected to come back and find him frozen or starved or something.

Instead, the bucket had moved across the basement, and there were the remains of a couple of rats scattered around. He hadn’t eaten the bones. That was how we figured out that Bob could feed himself. I’m still not sure how he moves—like a slime-mold maybe. I’m not going to pick the bucket up and find out. I doubt there’s a bottom on it any more, but I don’t want to risk annoying Bob.

He likes me best, maybe because I feed him the most often. He tolerates Aunt Tabitha. My uncle won’t go into the basement any more, he claims Bob actually hissed at him once. It would have been a belching sort of hiss, I imagine.

I dumped the flour in on top of Bob, and he glubbed happily in his bucket and extended a sort of mushy tentacle. I pulled it off, and the starter settled back and began digesting the flour. He doesn’t seem to mind me taking bits to make bread, and it’s still the best sourdough in town.

Paladin's Strength

Paladin's Strength The Twisted Ones

The Twisted Ones The Hollow Places

The Hollow Places Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel

Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel Swordheart

Swordheart Jackalope Wives And Other Stories

Jackalope Wives And Other Stories A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking

A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking Minor Mage

Minor Mage The Halcyon Fairy Book

The Halcyon Fairy Book Bryony and Roses

Bryony and Roses The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War

The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War

Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War The Raven and the Reindeer

The Raven and the Reindeer Summer in Orcus

Summer in Orcus The Wonder Engine

The Wonder Engine Seventh Bride

Seventh Bride Toad Words

Toad Words Nine Goblins

Nine Goblins