- Home

- T. Kingfisher

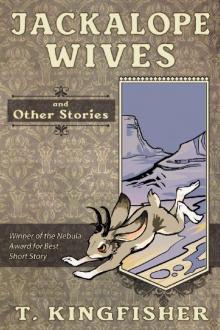

Jackalope Wives And Other Stories

Jackalope Wives And Other Stories Read online

CONTENTS

Copyright Information

Praise for T. Kingfisher

Dedication

The Kingfisher & The Jackalope

Godmother

Jackalope Wives

Wooden Feathers

Editing

Bird Bones

That Time With Bob And The Unicorn

Razorback

The Dryad's Shoe

Let Pass The Horses Black

This Vote Is Legally Binding

Telling the Bees

The Tomato Thief

In Questionable Taste

Origin Story

Pocosin

It Was A Day

Acknowledgments

Other Works

This is a work of fiction. Nothing is true, except for the bits that are, and even those don’t resemble anybody in particular.

Copyright 2017 Ursula Vernon

All Rights Reserved

Published in the United States by Red Wombat Tea Company

Artwork by Ursula Vernon

Praise for “Toad Words”

“…a book of re-told fairy tales, all in the quirky, matter-of-fact-in-the-face-of-total-nonsense style that I’ve always loved. They’re often dark, sometimes sad, but always endearing, even when they’re disturbing.”

—Pixelatedgeek.com

Praise for “The Seventh Bride”

“…[A] knack for creating colorful, instantly memorable characters, and inhuman creatures capable of inspiring awe and wonder.”

—NPR Books

Praise for “Bryony & Roses”

“The writing. It is superb. Ursula Vernon/T. Kingfisher, where have you been all my life?”

—The Book Smugglers at Kirkus Reviews

Praise for “The Raven & The Reindeer”

“…an exquisitely written retelling of Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen… I love this book with the blazing passion of a thousand suns. I'm sitting here almost crying at the thought that I had to wait until I was fifty-seven (almost fifty-eight!) years old before having a chance to read this book.”

—Heather Rose Jones, Daughter of Mystery

For Sigrid

who told me to write her a story

THE KINGFISHER & THE JACKALOPE

It was a few years ago now that I wrote a story for my friend Sigrid, during her stint as editor of Apex Magazine. I had agreed to write one with no idea what I was doing, and so I wrote it at a tattoo parlor, while my husband was getting ink etched into his skin, and that started something happening in my brain about skins, which turned into “Jackalope Wives.”

I had never submitted a short story for publication before. I hadn’t even thought about it. I hadn’t even thought that I was writing short stories, rather than fictional blog post thingies.

“Jackalope Wives” won a Nebula, and at the after-party, I wandered around in a kind of stunned haze. (I had been so confident of not winning that my speech had been prepared for the “alternate universe Nebulas” where authors deliver the speech from the alternate universe where they won. It’s a grand tradition, and I was excited to deliver my speech from the universe where I had won and also everyone was a giant chicken. I gazed out across a dinner crowd consisting of many of science fiction’s greatest luminaries, and heard myself say “Please hold your clucks until the end of the speech…”)

At this after-party, an editor from Uncanny Magazine said to me, “We gotta get a story from you!”

I said, “Uh. Okay? I can do that?” while thinking “Wait, really?” and then, much belatedly, “Wait, was that networking? Is networking a thing I just did?”

I am not exactly a marketing genius.

“Jackalope Wives” went on to win a couple more awards and Apex Magazine, perhaps unsurprisingly, wanted another story, which made two stories that people wanted and I had somehow agreed to provide. So I wrote two stories, in a bit of a panic, and then I was in a groove and wrote a couple more.

But what did I do with the new ones? I couldn’t just bombard these poor people with submissions, could I? That seemed like stalker behavior or at very least entitled—“Hey, you bought a story once, now I will send you ALL OF THEM FOREVER!”—or possibly just sad, like the way that our old Border Collie chased a raccoon up a tree once years ago and always visited that tree first in the yard, forever after, in case the raccoon came back.

And then it occurred to me that I could send a story to a market who hadn’t said “Send us a story!” first and maybe they would not send me a pipe bomb by return mail and if they hated it, it wouldn’t be weird.

Some of those sold, too. Not all of them, but a couple. My plan seemed to be working—so long as I never submitted anywhere twice, it wouldn’t be awkward.

This is not the way to start a short-story career, nor even to blunder into one in midstream. Eventually the editors caught up with me and would start ordering me to send them my next story. Or they would pop up with “I really need a novelette for this fundraiser, what have you got?” and then I was Helping Them With A Problem, not Bothering This Busy Person Who Was Nice To Me Once, Probably Out Of Pity.

My cover letters said things like “Here is a thing and I said I’d write you a thing but you don’t have to publish it but it’s yours if you want it but if not, I’ll write you a different one.”

I’ve gotten slightly better at that bit, but not much.

So here is a collection of short stories, which were mostly published elsewhere over the last couple years, but I am putting them all in one place because people asked. I have also included a couple of new ones, because if you’re going to lay out money for a collection, you ought get something spiffy and new out of it.

(I am writing this introduction right now in a coffee shop, during a heavy rainstorm, and they are playing Tom Waits. I feel a sort of cheerful, gritty desolation, like smoking the last cigarette at the end of the world. Some of these stories are like that and some of them are funny and some are hard and some are odd, but maybe you’ll find something to enjoy.)

Well. Here is a thing, but you don’t have to read it, but it’s yours if you want to. And if not, I’ll write you some different ones.

T. Kingfisher (Ursula Vernon)

Pittsboro

April 2017

GODMOTHER

To this day, I still wonder a bit about the bone dog and where it came from. It seems like a book I should write someday.

You came to me in your cloak made of tatters, with the dog made of bone at your side.

You came to me and demanded to know why—why hadn’t I been there? Why her, and not you?

What had she done to earn fairy gifts to smooth her way? What did she do to earn the golden dresses and the silver shoes, the care of old women and the kindness of princes?

Why did she get to dance, when you had to carve your path of thorns, and bleed for every inch?

I told you that fairy godmothers are a little less than angels. We are given only enough power to hold in our two hands. There is not enough to go around.

I told you that we spend it very grudgingly, and only on those who cannot succeed without our help.

The dancing princess would have died. She would have withered at the first harsh word. She could never have woven the rope from nettles, or built her own dog out of bones.

So I helped her and not you.

I told you that even in the cradle, I knew that you were strong.

You swallowed that, even though the taste was bitter. You were already proud of your strength. (And why wouldn’t you be? You have done amazing things. I wish I had the right to be proud of what you’ve done.)

You walked away, with yo

ur tattered cloak swinging, with the bone dog clattering at your side. You walked away, and all you left was the handprint on the doorframe, with your left hand stained with the prince’s blood.

I watched you go, and picked the bits of lie out of my teeth with the tip of a worrying tongue.

Truth is, there are too many broken people in the world.

We bet on the ones we think will make it, like birds who feed the strongest chick. We pour love out on those who are already loved and magic on those who only need a little, since a little is all we have to give.

There was nothing much to recommend you as a child. You squalled and whined and cried. You were timid and afraid of strangers.

(And I have to tell you that your breathing was annoying, you made little “uhn! uhn!” noises in your throat at every breath, and certainly this is petty but also it is true.)

Mostly, though, you were easy to forget, so I forgot you.

I did not expect you to survive. You should have died a dozen times and yet you lived, for all you went a darker way.

Well. Good for you. We don’t always get it right.

I waited too long to clean the handprint off the doorframe. I left it there for days as a reminder. My eyes dragged over it every time I went out.

I think I hoped that I would learn something.

In the end I washed it off, or tried.

The white paint underneath is stained. In sunlight I hardly notice.

But sometimes now, before I light the candles, I see the shadow of your hand against the door.

JACKALOPE WIVES

The moon came up and the sun went down. The moonbeams went shattering down to the ground and the jackalope wives took off their skins and danced.

They danced like young deer pawing the ground, they danced like devils let out of hell for the evening. They swung their hips and pranced and drank their fill of cactus-fruit wine.

They were shy creatures, the jackalope wives, though there was nothing shy about the way they danced. You could go your whole life and see no more of them than the flash of a tail vanishing around the backside of a boulder. If you were lucky, you might catch a whole line of them outlined against the sky, on the top of a bluff, the shadow of horns rising off their brows.

And on the half-moon, when new and full were balanced across the saguaro’s thorns, they’d come down to the desert and dance.

The young men used to get together and whisper, saying they were gonna catch them a jackalope wife. They’d lay belly down at the edge of the bluff and look down on the fire and the dancing shapes—and they’d go away aching, for all the good it did them.

For the jackalope wives were shy of humans. Their lovers were jackrabbits and antelope bucks, not human men. You couldn’t even get too close or they’d take fright and run away. One minute you’d see them kicking their heels up and hear them laugh, then the music would freeze and they’d all look at you with their eyes wide and their ears upswept.

The next second, they’d snatch up their skins and there’d be nothing left but a dozen skinny she-rabbits running off in all directions, and a campfire left that wouldn’t burn out ‘til morning.

It was uncanny, sure, but they never did anybody any harm. Grandma Harken, who lived down past the well, said that the jackalopes were the daughters of the rain and driving them off would bring on the drought. People said they didn’t believe a word of it, but when you live in a desert, you don’t take chances.

When the wild music came through town, a couple of notes skittering on the sand, then people knew the jackalope wives were out. They kept the dogs tied up and their brash sons occupied. The town got into the habit of having a dance that night, to keep the boys firmly fixed on human girls and to drown out the notes of the wild music.

Now, it happened there was a young man in town who had a touch of magic on him. It had come down to him on his mother’s side, as happens now and again, and it was worse than useless.

A little magic is worse than none, for it draws the wrong sort of attention. It gave this young man feverish eyes and made him sullen. His grandmother used to tell him that it was a miracle he hadn’t been drowned as a child, and for her he’d laugh, but not for anyone else.

He was tall and slim and had dark hair and young women found him fascinating.

This sort of thing happens often enough, even with boys as mortal as dirt. There’s always one who learned how to brood early and often, and always girls who think they can heal him.

Eventually the girls learn better. Either the hurts are petty little things and they get tired of whining or the hurt’s so deep and wide that they drown in it. The smart ones heave themselves back to shore and the slower ones wake up married with a husband who lies around and suffers in their direction. It’s part of a dance as old as the jackalopes themselves.

But in this town at this time, the girls hadn’t learned and the boy hadn’t yet worn out his interest. At the dances, he leaned on the wall with his hands in his pockets and his eyes glittering. Other young men eyed him with dislike. He would slip away early, before the dance was ended, and never marked the eyes that followed him and wished that he would stay.

He himself had one thought and one thought only—to catch a jackalope wife.

They were beautiful creatures, with their long brown legs and their bodies splashed orange by the firelight. They had faces like no mortal woman and they moved like quicksilver and they played music that got down into your bones and thrummed like a sickness.

And there was one—he’d seen her. She danced farther out from the others and her horns were short and sharp as sickles. She was the last one to put on her rabbit skin when the sun came up. Long after the music had stopped, she danced to the rhythm of her own long feet on the sand.

(And now you will ask me about the musicians that played for the jackalope wives. Well, if you can find a place where they’ve been dancing, you might see something like sidewinder tracks in the dust, and more than that I cannot tell you. The desert chews its secrets right down to the bone.)

So the young man with the touch of magic watched the jackalope wife dancing and you know as well as I do what young men dream about. We will be charitable. She danced a little apart from her fellows, as he walked a little apart from his.

Perhaps he thought she might understand him. Perhaps he found her as interesting as the girls found him.

Perhaps we shouldn’t always get what we think we want.

And the jackalope wife danced, out past the circle of the music and the firelight, in the light of the fierce desert stars.

Grandma Harken had settled in for the evening with a shawl on her shoulders and a cat on her lap when somebody started hammering on the door.

“Grandma! Grandma! Come quick—open the door—oh god, Grandma, you have to help me—”

She knew that voice just fine. It was her own grandson, her daughter Eva’s boy. Pretty and useless and charming when he set out to be.

She dumped the cat off her lap and stomped to the door. What trouble had the young fool gotten himself into?

“Sweet Saint Anthony,” she muttered, “let him not have gotten some fool girl in a family way. That’s just what we need.”

She flung the door open and there was Eva’s son and there was a girl and for a moment her worst fears were realized.

Then she saw what was huddled in the circle of her grandson’s arms, and her worst fears were stomped flat and replaced by far greater ones.

“Oh Mary,” she said. “Oh, Jesus, Mary and Joseph. Oh blessed Saint Anthony, you’ve caught a jackalope wife.”

Her first impulse was to slam the door and lock the sight away.

Her grandson caught the edge of the door and hauled it open. His knuckles were raw and blistered. “Let me in,” he said. He’d been crying and there was dust on his face, stuck to the tracks of tears. “Let me in, let me in, oh god, Grandma, you have to help me, it’s all gone wrong—“

Grandma took two steps back, while he h

alf-dragged the jackalope into the house. He dropped her down in front of the hearth and grabbed for his grandmother’s hands. “Grandma—”

She ignored him and dropped to her knees. The thing across her hearth was hardly human. “What have you done?” she said. “What did you do to her?”

“Nothing!” he said, recoiling.

“Don’t look at that and tell me ‘Nothing!’ What in the name of our lord did you do to that girl?”

He stared down at his blistered hands. “Her skin,” he mumbled. “The rabbit skin. You know.”

“I do indeed,” she said grimly. “Oh yes, I do. What did you do, you damned young fool? Caught up her skin and hid it from her to keep her changing?”

The jackalope wife stirred on the hearth and made a sound between a whimper and a sob.

“She was waiting for me!” he said. “She knew I was there! I’d been—we’d—I watched her, and she knew I was out there, and she let me get up close—I thought we could talk—”

Grandma Harken clenched one hand into a fist and rested her forehead on it.

“I grabbed the skin—I mean—it was right there—she was watching—I thought she wanted me to have it—”

She turned and looked at him. He sank down in her chair, all his grace gone.

“You have to burn it,” mumbled her grandson. He slid down a little further in her chair. “You’re supposed to burn it. Everybody knows. To keep them changing.”

“Yes,” said Grandma Harken, curling her lip. “Yes, that’s the way of it, right enough.” She took the jackalope wife’s shoulders and turned her toward the lamp light.

She was a horror. Her hands were human enough, but she had a jackrabbit’s feet and a jackrabbit’s eyes. They were set too wide apart in a human face, with a cleft lip and long rabbit ears. Her horns were short, sharp spikes on her brow.

Paladin's Strength

Paladin's Strength The Twisted Ones

The Twisted Ones The Hollow Places

The Hollow Places Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel

Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel Swordheart

Swordheart Jackalope Wives And Other Stories

Jackalope Wives And Other Stories A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking

A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking Minor Mage

Minor Mage The Halcyon Fairy Book

The Halcyon Fairy Book Bryony and Roses

Bryony and Roses The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War

The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War

Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War The Raven and the Reindeer

The Raven and the Reindeer Summer in Orcus

Summer in Orcus The Wonder Engine

The Wonder Engine Seventh Bride

Seventh Bride Toad Words

Toad Words Nine Goblins

Nine Goblins