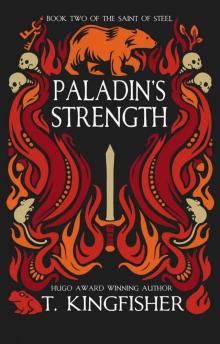

Paladin's Strength

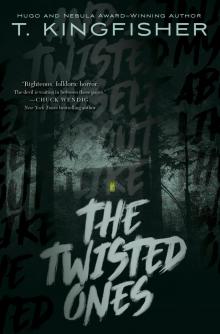

Paladin's Strength The Twisted Ones

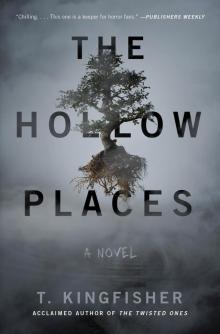

The Twisted Ones The Hollow Places

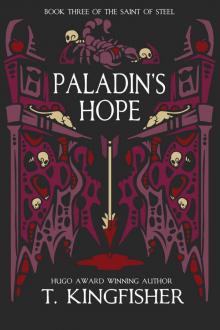

The Hollow Places Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel

Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel Swordheart

Swordheart Jackalope Wives And Other Stories

Jackalope Wives And Other Stories A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking

A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking Minor Mage

Minor Mage The Halcyon Fairy Book

The Halcyon Fairy Book Bryony and Roses

Bryony and Roses The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War

The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War

Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War The Raven and the Reindeer

The Raven and the Reindeer Summer in Orcus

Summer in Orcus The Wonder Engine

The Wonder Engine Seventh Bride

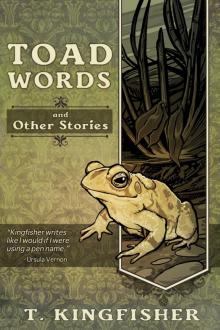

Seventh Bride Toad Words

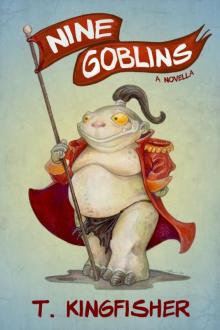

Toad Words Nine Goblins

Nine Goblins