- Home

- T. Kingfisher

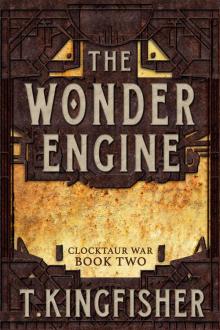

The Wonder Engine Page 9

The Wonder Engine Read online

Page 9

“You should have told us that you were at risk.”

Slate threw her hands in the air. “Oh, like you’ve been so forthcoming? Forgive me if I’m not rushing to tell everyone all about my past! Hell, I still don’t know how you wound up with a demon in your head, but am I lecturing you about it?”

She folded her arms and glared at him.

And now he’ll point out that it doesn’t matter if he ends up dead because he’s not terribly essential now that he got us to Anuket City and he’ll probably be right. Dammit. I don’t want to be essential.

Caliban took a deep breath, let it out, and clasped his hands behind his back. He stared at the floor.

Oh god, he’s in parade rest again. Why is this my life? Slate rubbed a hand over her face.

“Pride,” said Caliban.

He seemed to be waiting for a response. Slate said, “Err, what?”

“Pride,” said Caliban. “It’s a sin. In my case, a mortal one.”

“…okay?”

He lifted his eyes to her face. “No. I have not been forthcoming. It is not a story that reflects well on me.”

Slate sighed. She was tired and her feet hurt and she was about to learn something that was undoubtedly going to be unpleasant.

She couldn’t do the voice, but there were still things a decent person could do. Even if I’m not a paladin.

She moved her aching feet to one side and said, “Sit down.”

“I—”

“It’s a liege…order…thing.”

He sat.

“All right. Let’s hear it.”

“When you fight a demon,” said Caliban, “if it’s in an animal, you kill it. If it’s a person, you bind it and take them back to the temple for exorcism, if you can.” He studied the floor again. “If you can’t bind it, you kill them. Paladins on the temple’s errands are immune from murder charges, did you know that?”

“Ah,” said Slate. “That explains why they didn’t...”

“Hang me? Yes. Technically I was still on duty, so killing ten people was legal for me.” He made the bitterest sound she’d ever heard from a human throat.

Slate dragged her aching feet cross-legged and put her chin in her hand.

“That said…there are times when we bend the rules a little.”

Is he expecting me to gasp with shock?

“If someone is very young or very frail, we will try to exorcise the demon there, if we can. Exorcism is hard and it is not made easier by dragging them fifty miles in chains.”

Slate, who had been dragged approximately two hundred yards in chains some weeks earlier, could see how difficult it might be. And that was inside the Dowager’s palace, and they took them off as soon as I agreed to go on this wild goose chase. Yeesh.

He said nothing for a few moments. Slate finally said “And…?”

Caliban looked up at the ceiling. His voice became flat and detached, like a man making a report to a superior officer. Which, I guess, he is.

“Exorcisms are always done in pairs. It’s a formality. Usually a formality. You bind and then you exorcise. If the demon comes unbound and jumps and finds a foothold in the one doing the exorcism, the second priest—or paladin—is supposed to catch it. That never happens, though. Once bound, a demon becomes obedient.”

Slate nodded. “Not a formality this time, huh?”

Caliban shook his head. “I had done dozens of bindings by now, you understand. Mostly of animals, but still. It wasn’t hard. My heart was pure. Demons trembled at my name.”

He didn’t say it like he was boasting. He didn’t say it sarcastically. He said it like it was true.

Slate had surprisingly little trouble believing him.

“And then I had a case of an infant possessed. The mother was begging me to save it. The infant…well, the priestess I was working with had broken her leg the week before and I was a long day’s ride from anywhere. Demons aren’t easy on their hosts, and it was half-dead already. I thought there was little chance I’d get it to the temple alive, and less that it could survive the exorcism, but if I did the rite right there…” He put his head in his hands.

“Didn’t work?”

“Oh, it worked,” said Caliban. “It worked beautifully. I breathed life back into that half-dead child and the demon went back to hell with a will and I felt smug with a job well done. And then the one that had been in the mother jumped, while my soul was wide-open and I was wallowing in my own pride.”

Slate winced.

He dropped his hands. In a more normal voice, he added, “I still don’t really know how the demon did it. They can pass very well for human if the human hosting them agrees to it, but they hate being near each other. I think it must have caught and bound the first one to bait the trap—it was smart. And very strong.” He snorted. “That’s the temple’s judgment, not mine, incidentally. It took three priests and four tries to kill it, and they couldn’t get it all. You know all the rest.”

“You were trying to do the right thing,” said Slate.

He sighed again. “No. Self-justification doesn’t survive an exorcism. I was trying to be a hero, and convinced that I was more righteous than other paladins before me. That I was holy enough to break the rules. And I should probably have told you all that the first day.”

“Well,” said Slate. “Neither of us was at our best.”

“There’s that.”

She scratched the back of her neck irritably. And now I suppose I have to do something gracious, having learned an object lesson about the dangers of arrogance. Damn him, anyway. And it was all entirely earnest and entirely true, that’s the worst of it.

That was the trouble with genuinely honorable people. You just couldn’t get any traction at all.

“So…that’s when you had your crisis of faith?” she asked, to buy time.

“My what?” He looked so blank that it left Slate feeling nonplussed, as if she had misunderstood something vital.

“You said, back when we met, that you thought your god had abandoned you…?”

“Yes,” said Caliban. “But that’s…no. A crisis of faith is what you have when you’re a teenager and wonder if the gods even exist. Or you’re a middle-aged priest and you question the teachings of your religion and the problem of suffering and how futile everything seems. Something like that. Me, I kill demons.”

“Well, la-di-dah,” muttered Slate.

He actually smiled. “It’s remarkably straightforward. The Dreaming God is not a terribly prescriptive god. Very few commandments. We don’t even go in for prophets very much. We just try to stop demons before they can do too much harm.”

“There are worse philosophies, I guess.”

“I cannot question the existence of the Dreaming God. I felt His presence for many years. It is only by His grace that we humans can bind demons at all.”

“So when you say He abandoned you…?”

The smile faded. “Exactly that. It seems that He will not or cannot share a soul with a demon.”

“He won’t?” Slate was starting to feel like the stupid one in this conversation, as if she were trying to have a conversation about machinery with Learned Edmund that started with, ‘So, gears, do you know they exist?’

“I am uniquely qualified to comment, and no. I have not felt His presence since the demon took me.”

He sounded so calm about it. Somehow that made it worse.

“But all that praying you do…”

Caliban shook his head. “Prayer is for the one who prays. It would be a monstrous arrogance to think that my prayers might sway the heart of a god.”

Much more of this, and he’s going to start apologizing to the gods in front of me. I can’t take it.

He’s also not going to leave until he gets an answer.

She glared at him. He sat there, hands folded, apparently willing to sit in silence until the end of the world, if that was what his liege required of him.

God’s stripes, as Grimehug wo

uld say.

“I can’t swear that I won’t have follow some leads on my own,” she said finally, “but—when possible—I will take an escort. Grimehug or Brenner or you.”

Caliban nodded. He seemed relieved to change the subject. “Grimehug is a good choice. I doubt he will be noticed, and he can at least bring us word.”

She should have left it there. She knew that she should leave it there. But—

“Not Brenner, eh?”

Caliban would not meet her eyes.

Slate waited.

“I don’t like the way he looks at you.”

Slate raised her eyebrows. Was this jealousy, or something less? “I may not look like my mother,” she said mildly, “but men do look at me occasionally.”

Caliban shook his head, lifted a hand. “Not like that. It’s not…normal.”

Her eyebrows climbed higher. “What, does one of his eyes pop out or something?”

“I’m serious.”

“Trying to keep me from doing something I’ll regret again?”

Caliban flinched.

After a moment, he said, “Madam—Slate—if you don’t trust me as a knight, then trust me as a man. We recognize these things in each other. The way he looks at you has no love in it, and too much hunger.”

Her laughter came out in a short, painful bark. “Well, there’s little enough love in Brenner, that’s true.” Lust, yes. Even passion, if memory serves. But there’s not much call for assassins who can love.

Caliban sighed, and his shoulders slumped. “Forget I said anything. It’s not my place.” He turned away.

“No—wait—” She reached out and caught his forearm, and he halted. “I’m sorry. You’re just trying to look out for me. You may even be right that I should have told you all about Horsehead. Fine. But I don’t know what else I can say—we need Brenner for this. You know we do.”

He nodded slowly, looking down at the hand on his arm. She let him go.

“Besides,” she said, trying to make light of it, “there’s no crime in looking.”

“No,” said Caliban. He raised his eyes to meet hers. “I’m glad.”

His were very dark in the candlelight and very deep and there was a great deal of hunger in them. And something more than that.

He left the room before she could think of anything to say.

Slate stared at the door long after it had closed behind him.

She didn’t know if she should laugh or burst into tears. And she had no idea what, if anything, to do about it.

Seventeen

Slate was watching gnoles.

She sat cross-legged on the roof of the inn, in the shadow of one of the chimneys. Grimehug was not with her, but that was because the inn would have gotten very upset if there was a gnole on the roof.

It was a perfectly good reason and she would tell Caliban that if he tried to lecture her about it.

Am I being petty? It’s possible I’m being petty.

Serve him right for…for looking at me like that! And then stomping off to go brood somewhere. Goddamn paladins.

She wouldn’t have been half so annoyed if he hadn’t had a valid point about the risks.

How dare he tell me about his awful past at a particularly relevant moment? The nerve of the man!

Slate grinned sourly to herself.

Gnoles moved through the streets below, small, rag-wrapped figures. They mostly stayed out of the way of the humans, keeping to alleys and shadows—but they didn’t hide.

Slate had to admire the technique.

The gnoles weren’t doing anything to avoid being seen. Instead, they were moving like they belonged there, going somewhere, doing some small, vital, probably disgusting task.

For someone who staked her life on being overlooked, it was like watching masters at work. In the Dowager’s city, being short and female and dark-skinned made people’s eyes slide over you, but it was nothing compared to the gnoles.

Being invisible nearly drove me mad, until I learned to use it to rob people blind. I wonder how the gnoles manage. Do they ever wish that they weren’t invisible?

They weren’t human. She had to remind herself of that. Perhaps the gnoles did not care what humans thought, because they weren’t invisible to each other.

Rag-and-bone gnoles. Grave-gnoles. There’s some kind of class system, to hear Grimehug talk, even if they don’t have kings. But regardless, they’re all doing nasty little jobs that humans don’t really want to do.

And nobody looks too closely at them.

And I bet nobody knows how many there are.

Over the course of an hour, Slate counted several dozen. Probably she counted a few twice, but still, there were lots of gnolls out, even relatively early in the morning.

There could be thousands in the city. I’d be a little surprised if there weren’t.

She didn’t wonder what they were eating. She’d already seen a gnole pounce on an unwary pigeon and scurry off with it.

I bet the rat population is way down. And the feral dogs and the feral cats…

Good thing Grimehug’s on our side.

Slate picked at a loose thread on the side of her trouser leg.

Assuming…of course…that he is on our side. But no. There’s no way you’d plant somebody in the middle of a rune village in the Vagrant Hills to try to throw spies off the track. He’s told us too much, and we’ve verified most of what he’s said.

I suppose he could still decide to sell us out. He worked for the merchants, after all. It could be in his best interest to keep the clocktaurs around.

He seems pretty bitter about them, though. Particularly since they left his friend to die, and the rune caught him.

A ragged pair of gnoles cross the square across from the inn. They were dressed more drably than Grimehug, in grays and browns.

Rag-and-bone gnoles, I think…

The rag-and-bone gnoles dug in the gutters, moving out of the way if a human came near. They reminded Slate of crows settling on something dead.

Nothing wrong with that. Be a much nastier world if not for crows.

Come to think of it, the city did seem cleaner than it had when she’d lived here…

Of course. You don’t have to pay gnoles what you pay humans. The Senate probably loved that. The Merchant’s Guild, too. The city gets cleaned up and you can cut an entire segment of the payroll…and they’ll eat the rats and the cats and the rest of the vermin. Who wouldn’t want gnoles?

She chewed on her thumbnail. Innkeepers, apparently.

Do they really carry werkblight? Wouldn’t I have it by now?

But I saw blight in the Dowager’s city, too. If it’s the same thing, where did it come from?

The rag-and-bone gnoles finished their sweep of the gutters and scurried away down an alley.

Grimehug had said something about gnoles in the capitol, so it was possible. They’d found no pattern to the deaths in the capitol, but they also hadn’t been looking for gnoles. Nobody knew they existed.

They’d just be some ratty little critters living in alleys by the docks…nobody’d pay much attention down there…half the merchants do business in Anuket anyway, so they’d be used to seeing them…

More gnoles, in brighter clothing, moved through the square. Three of them laughed together, then split apart and went three separate ways. A man went through on one of the wrought-iron artifact horses and nearly ran over one, not looking, not seeing.

No, it can’t be gnoles. If they were the ones carrying werkblight, everybody in Anuket City would have it by now. The guards by the factory would have it. The Merchant’s Guild would have thrown them all out. I don’t care what the innkeepers think, there’s gnoles everywhere.

A knot of white-clad gnoles entered the square.

Slate sat up, interested.

They were dragging a dog-cart behind them. Two gnoles were pulling it along and two more walked behind the cart—and people saw them.

Humans drew back when they

approached. The rider on the artifact horse turned his steed sharply and went down another street.

They halted outside a small building and waited. Their wrappings were pale, marred with dust and darker things.

Are they wearing burial shrouds?

What did Grimehug say? Rag-and-bone gnoles, job gnoles, grave-gnoles…

There was no mistaking which these were.

One of the grave-gnoles tapped on the door and waited.

Someone wailed from inside the house. A woman came to the door and held it open. Slate was too far away to make out her expression, but the set of her body was grim.

The two grave-gnoles went silently into the house.

The square emptied entirely of humans. Even the other gnoles pulled back into the alleyways.

The door opened again. The grave-gnoles carried a bundle between them, wrapped in blankets.

Slate didn’t have to be on ground level. There was only one thing that was ever that shape.

The grave-gnoles loaded the body into the dog-cart and pulled it away.

After a few minutes, the square began to fill up again, but Slate wasn’t around to see them, because she was hurrying over the rooftops in hot pursuit.

Eighteen

The grave-gnoles could not take the narrowest alleys, because of the dog-cart, so their path across the city was a roundabout one. Slate disliked the rooftops in daylight. People didn’t look up much, but when they did, they tended to point.

Still, there were a couple of chimney sweeps about, and even a few gnoles raiding pigeon nests. The sweeps eyed her oddly. The gnoles ignored her.

She kept an eye on the dog-cart, although she had a sudden suspicion that she knew where it was going.

They passed into the Old City. The buildings got shorter and the roof tiles changed underfoot. Slate had to pick her way carefully, dividing her attention between her footing and the grave-gnoles.

They turned once—twice—and then Slate pulled up short. She dropped to a crouch and watched the cart rumble away through the streets.

The grave-gnoles were taking the corpse into the Clockwork District. Slate closed her eyes and listened intently—was that the sound of the gate being opened?

Paladin's Strength

Paladin's Strength The Twisted Ones

The Twisted Ones The Hollow Places

The Hollow Places Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel

Paladin’s Hope: Book Three of the Saint of Steel Swordheart

Swordheart Jackalope Wives And Other Stories

Jackalope Wives And Other Stories A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking

A Wizard's Guide to Defensive Baking Minor Mage

Minor Mage The Halcyon Fairy Book

The Halcyon Fairy Book Bryony and Roses

Bryony and Roses The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War

The Wonder Engine_Book Two of the Clocktaur War Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War

Clockwork Boys: Book One of the Clocktaur War The Raven and the Reindeer

The Raven and the Reindeer Summer in Orcus

Summer in Orcus The Wonder Engine

The Wonder Engine Seventh Bride

Seventh Bride Toad Words

Toad Words Nine Goblins

Nine Goblins